Old Blind Joe Death – I read somewhere that Fahey released music under that name sometimes, and convinced a musicologist that they were listening to an old blues man. But this was a middle class Berkeley flunking man, whose life had become overtaken by the sounds he could make with the guitar. In pursuit of something it feels like, Often with this wandering rhythm over which melodies and counter melodies drift in and out. Big Beard, the man was a mystic, sometimes he sounds like he has found something when he is playing, and that he is playing from somewhere else. I feel like that anyway, joining him in his cascades of finger-picked notes.

We used to visit my dad and burn CDs of things that we liked as we listened to them with him in his room. He had special pens for writing on CDs and sometimes I would try to copy the fonts from the front of the albums when I wrote down the names of the bands and albums on to the front of the CD and its case. He played us a CD by Fahey, I don’t think I’d heard anything quite like it. The mesmeric sound, the resonance as he worked on his guitar, sometimes through familiar tunes, other times through melodies that sound like crisp new ideas, with hectic rhythms and counterflows that move past like thought .

Fahey slipped off the radar in the seventies and eighties, he lost touch with daily life as he drank more. Eventually, washed up, he was living in cheap motels and pawning records and guitars to pay for his life. I imagine his beard grew, I imagine his waistline grew, I imagine he lost touch with one friend after another. But he must have still been playing, because when he found that he had acquired a cult status without him fully realising it he was coaxed out into music-making again.

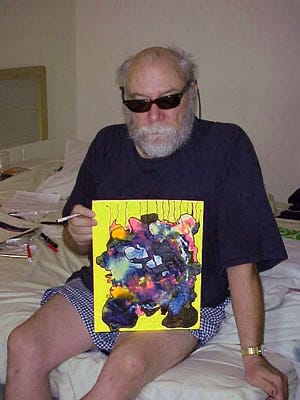

He also found other things to do when he was in exile, in particular he made paintings, with no apparent intention of selling them. I do not get the sense that being a businessman was his forte. He apparently gave some up in the late nineties in exchange for a collection of Duke Ellington records. They won’t have had much value but I suppose the other person had faith in Fahey’s name. It seems like Fahey was unwilling to live according to the conventions of the world he lived in. He dropped out of his Philosophy degree, I wonder if he wrote difficult and stubborn essays which enraged his tutors as I have found in Trevor’s papers. But there is a sweetness to Fahey which I did not often feel from my father, at least not until his last years. Or is that in the music only?

Fahey’s music is beautiful for the fact that it is at once utterly focussed in on itself, and as expansive as the sea. You can hear the concentration, and the uncompromising attention to the work he is doing in the recordings that he made. Perhaps it is for this reason that the moment I think of most often is the penultimate song on his Album The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death, called Poor Boy. In it he sets off at an ululating trot for a handful of bars before he is interrupted by a dog barking. We hear him stop, and he says ‘shh… sh’ and the dog stops, and he starts again. His music at once so much of the world, and so capable of silencing all around it.

I am writing this on an aeroplane to America, I am flying with Rebecca, and Sarah my Sister-In-Law. We are heading for Arkansas, where my brother is, and where I am yet to visit. Now I listen to Fahey’s 1971 album, America. The slow and ponderous rendition of Amazing Grace the melody treads carefully above an almost funereal base note. Fahey was one of those white men of the sixties and seventies who led the folk ‘revival’ partly inspired by all the black musicians and folk songs that they heard recorded by musicologists like Harry Smith. America is thoughtful though, it picks carefully and respectfully through the bones of the United States. It would be an ideal soundtrack for Charles Portis’ True Grit, set in Arkansas, which tells a story of the South which is at once full of cynicism, hope, and despair.

I have become a victim of magical thinking in the weeks and days since my Dad died. I have inadvertently inherited his eye for coincidence and the mystical. So in the volume of W.B. Yeats’ poems selected by Seamus Heaney, which I have brought to read while I am high up, I have begun to draw all kinds of fanciful lines of connection between Fahey, Yeats, and Trevor. I bought the book in Owl Books near where my Dad lived and I have spent days clearing out his flat. I bought it because as I have begun to flick through his notebooks I keep finding references to the poem The Second Coming. Which appears to have been important to Trevor. That is often how he talks about it not that he is fond of it but that it is important, and it has had a role in his thinking since he first read it.

In the Introduction Heaney describes Yeats’ “extreme exploration of the possibilities of reconciling the human impulse to transcendence with the antithetical project of consolidation”. To be at once single minded and expansive, feels as if it gets at something truthful about writing and making art, at least as I see it. To dwell with the particular, to hear the dog bark, and to offer the reader a new space to think in at the same time. In The Second Coming, and the famous image of the falcon:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The bird who flies free of its owner, turning and turning with no prospect of return. A suspension of relations as it wheels and wheels, and the centre fails. I don’t know well enough how to read poetry to be clear whether Yeats has a view on this, is this a good situation or a bad one? Or is it interim, a holding pattern like a plane circling before it lands.

‘The best lack all conviction, while the worst / are full of passionate intensity’ is this Yeats’ ideal, or is he warning us of it? Sometimes I felt that my father fit both of these, at once without conviction and full of intensity. Determined to fly freely loose from any centre to his life, but in doing so both giving up the particular and the transcendent. Just waiting, hoping for some revelation: ‘Surely the second coming is at hand’. I imagine my father thinking this to himself while he pored over an esoteric book, or pondered the I Ching, or the Tarot cards, or the Wiccan mirror, or the book of spells, or the box of stones, or the hollowed out birds eggs he had been given as a child which he felt so guilty about but kept his entire life, all of these things were in his flat. Which is now empty-ish, waiting for the contractors from the housing co-op to strip it all out and repaint it. Trying to clear out the smell, and evict the ghosts. One of the first of my Dad’s CDs which I listened to at home was Sonic Youth’s Rather Ripped and that perfect song which goes ‘do you believe in rapture, babe?’.

Later in life John Fahey came across a magazine article which proclaimed his influence for a number of musicians. Apparently having had no idea of this renewed interest he was sufficiently inspired to come back to recording music. In the nineties he fitted in well with the experimental musicians who had drawn on his music. His last album was released in 2003, two years after he died, it was around then that I was becoming interested in his music, I remember the cover of Red Cross, I remember turning it over in my hands at Trevor’s house. The last song on the album is called Untitled with Rain. A guitar, an organ, and a recording of rain, it sounds like its made on a city street, I hear cars passing with that crispy sweeping sound that tyres make on a wet road, occasionally some chimes sound. It is plaintive, maybe weary. The organ shimmers in expectation, the guitar is asking something of the nighttime sounds that receives no answer, a questioning dog with no one to quieten it with a shh.. It creates a sense of endless space but it is always happening right there in its rainy soundscape. Just before it hits five minutes someone says ‘hey there John’ and he just keeps playing. After six or so minutes it fades into silence for the remaining twelve minutes of the track.

I think my dad felt affinity with stubborn mystics like Yeats and Fahey. People with a sort of shamanic sense of purpose, of crossing between here and some other there. But when one feels that the centre cannot hold it is easy to become untethered altogether. To lose a sense of the things in life that one ought to attend to still even as you search out something else altogether. I mean me and my brother. In his art, and writing, and reading my dad was always adventurous and obsessive. But I think he forgot altogether the yapping dogs and the sounds of cars passing outdoors. It was just him. I think when he was young he believed that his talent would simply be discovered; but had he have been able to keep one foot in the real world, he might have known what it meant to try to leave it behind.